In the autumn of 1918, a global influenza outbreak began that would claim more lives than World War I (or the Great War). The war itself, which ended in November 1918, had a significant impact on how the virus spread around the world – and even influenced the name Spanish Flu.

There was nothing particular ‘Spanish’ about the flu: it didn’t begin in Spain and, while the country was badly affected, it wasn’t hit any harder than others. (The first wave spread in US military camps in 1917.)

However, Spain remained neutral during the conflict and its papers freely reported the outbreak. Media in France, the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States and elsewhere played down the impact on their own country in a bid to keep up morale. Newspapers were either directly controlled by national governments or keen to self-censor in the interest of patriotism at a time of war. They all happily reported on events in Spain – leading many to incorrectly presume that the Iberian Peninsula was the epicentre.

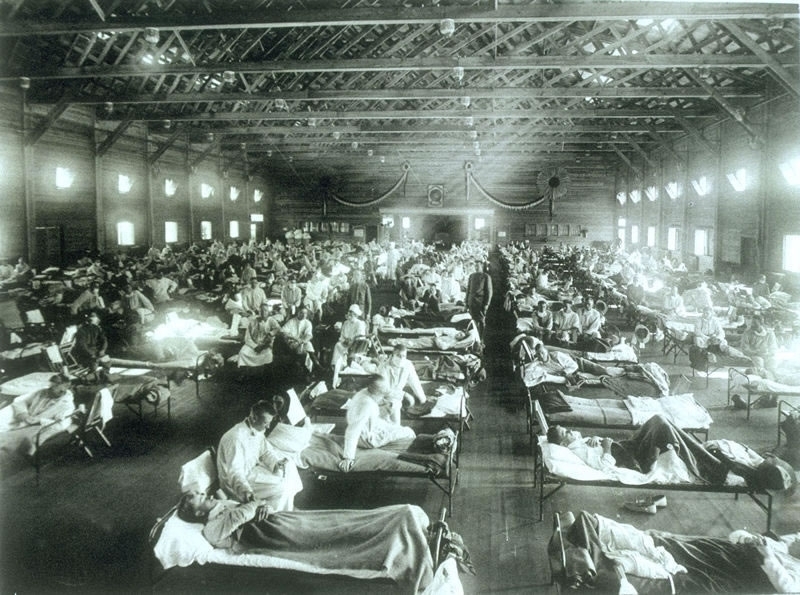

In summer of 1918, the virus spread among military units who lived in cramped quarters. And, as the war ended, surviving solders returned home – bringing influenza with them.

After four gruelling years of conflict, the immediate post-war period was a time for celebration. Public gatherings present an ideal opportunity for infectious diseases to find new victims. This most likely prolonged the second wave of the outbreak.

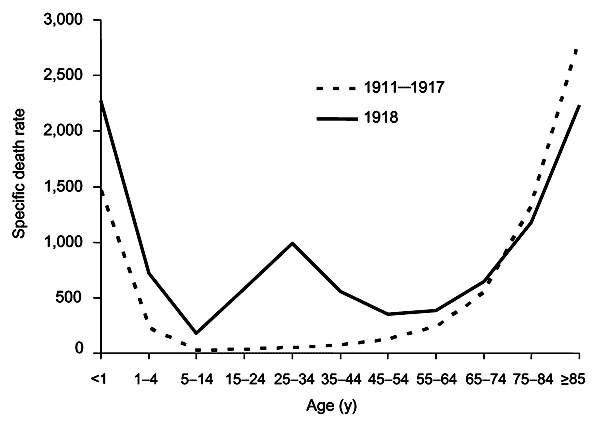

A third wave in the early spring of 1919 took war-weary populations by surprise, claiming millions more lives. Just as with seasonal influenza, the worst-hit populations were the very old and the very young. However, in comparison to a typical flu epidemic, there was a major spike in the 25-34 age group. Many soldiers who survived the trenches, did not survive the flu. Some returning soldiers shared the lethal virus with their spouses, also helping to push up the fatality rate in young adults.

There are a number of other reasons why the proportion of deaths among young adults was higher than normal. For one thing, the older population had partial immunity from the 1889-1890 flu pandemic (known as Russian flu).

The virus has also been shown to have triggered what is known as a ‘cytokine storm’ – an immune response that can be particularly severe in those with stronger immune systems.

The worst-affected group of all were pregnant women. Of the pregnant women who survived, over one quarter is estimated to have lost the child.

(Pregnant women are the #1 priority for flu vaccination, according to the WHO.)

During the 1918-1919 pandemic, researchers tried to develop a vaccine. According to the History of Vaccines project, a number of vaccines were tested against Bacillus influenzae (now known as Haemophilus influenzae) as well as strains of pneumococcus, streptococcus, staphylococcus, and Moraxella catarrhalis bacteria. These bacterial vaccines had no chance of stopping the pandemic which, we now know, was caused by a new strain of the influenza A virus.

Where are we now?

In the 100 years since the Spanish flu outbreak, there have been four influenza pandemics: 1957-1958, 1968-1969, 1977-1978, and 2009-2010. None were as lethal as the 1918 outbreak.

However, annual outbreaks of seasonal influenza cause between 290,000 and 650,000 deaths per year globally. The death rates are lower because (a) vaccines are available (b) healthcare and hygiene is vastly superior than conditions a century ago and (c) the viruses that cause seasonal flu are less dangerous – and less likely to be fatal to those infected.

Nonetheless, flu viruses can change from one year to the next. Experts continue to worry that a new flu virus could some day emerge with the potential to cause the kind of destruction seen in 1918.

The WHO is warning that low uptake of seasonal flu vaccines in Europe, is leaving vulnerable people at risk should an outbreak occur. Fewer than one third of older people are vaccinated in half of the 53 countries making up the WHO’s European region.

In fact, vaccination rates among high-risk groups have fallen in the years since the 2009-2010 pandemic.

‘Vaccination is the most effective measure to prevent severe disease caused by influenza. However, according to our research, influenza vaccination uptake has been steadily declining in a number of countries in the European Region,’ says Dr Zsuzsanna Jakab, WHO Regional Director for Europe. ‘This is of serious concern now for people at higher risk of severe consequences, especially older people, and in the future potentially for the entire population, as the production of pandemic vaccines is closely linked to seasonal vaccine use.’

In the EU, health ministers have set a target of vaccinating 75% of citizens in high-risk groups. With the exception of the UK and the Netherlands who have met this goal and are consistently above or close to the target, most EU countries are a long way from reaching their goal.

‘All European Union Member States have signed up to the goal of reaching 75% uptake among older people and other vulnerable groups; however, these targets are not being reached,’ says Dr Andrea Ammon, Director of European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

As we prepare to mark the centenary of the worst flu pandemic in recorded history, it is time to step up efforts to improve flu vaccine uptake.

Older people at higher risk of death from influenza

The WHO estimates that over 44,000 people die annually of respiratory diseases associated with seasonal influenza in the WHO European Region, out of a total of up to 650,000 global deaths.

According to annual surveys for the ECDC and WHO, although 34,000 (over 75%) of these deaths in Europe are among people aged 65 years or above, vaccine uptake remains low in this group. Half the countries in the WHO European Region are vaccinating fewer than one in three older people.

As for the other at-risk groups:

- vaccination was generally recommended for people with chronic illnesses; however, coverage was below 40% in most countries;

- almost all countries recommended influenza vaccination for health-care workers, but the majority reported influenza vaccine uptake as being as low as 40%;

- in total, 90% of countries had vaccine recommendations for pregnant women in 2014/2015, compared with 40% before the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic; however, coverage overall was low, with half the countries reporting uptake below 10%;

- fewer than half the countries, most of them in eastern Europe, recommended influenza vaccination for young children; vaccination coverage ranged from less than 1% to 80%.