Around 200 million people are infected by malaria every year. Some survive, many do not. In fact, malaria kills 1,200 children per day.

Around 200 million people are infected by malaria every year. Some survive, many do not. In fact, malaria kills 1,200 children per day.

For decades, scientists have tried to find a vaccine which would protect against the mosquito-borne illness. Until very recently, that quest had been in vain.

Now, the European Medicines Agency has approved RTS,S (known as Mosquirix), the world’s first vaccine against a parasite.

What is malaria?

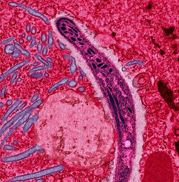

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected mosquitoes.

In 2013, malaria caused an estimated 584 000 deaths (with an uncertainty range of 367 000 to 755 000), mostly among African children.

Malaria is preventable and curable.

Increased malaria prevention and control measures are dramatically reducing the malaria burden in many places.

Non-immune travellers from malaria-free areas are very vulnerable to the disease when they get infected.

However, the vaccine is far from perfect. Effectiveness depends on whether children receive an additional booster shot after an initial three doses. This can be challenging in any circumstances, not least in sub-Saharan Africa.

Without the booster, protection falls from 36% to around 28% in older children – preventing around one in four cases. In younger children, the success rates can be even lower.

The question now is whether the possibility of saving one third or one quarter of those at the highest risk will be enough to convince World Health Organisation experts to recommend the vaccine for use in African countries.

The decision, as explained by this commentary from experts at the Global Fund and GAVI, the vaccine alliance, is complex.

<quote>If Mosquirix can potentially save lives or reduce illness now – even if only in one in three cases – then can we really justify holding off?</quote>

The problem is that it is not clear how exactly the vaccine will do in a real-world scenario. More data will be needed.

Other factors are also at play. If the vaccine works only in a minority of those who receive it, could it undermine faith in other vaccines?

Could it even lead to misplaced complacency among at-risk people who currently take mosquito-control measures such as bed nets and insect repellents?

<quote> The best way to get any clarity on these issues is to see how the vaccine performs in a real-life setting, in high and low transmission areas, with and without high coverage of other interventions.</quote>

For now, there is cautious optimism that science has taken the world one step closer to defeating one of the most stubborn and deadly foes we have ever faced.