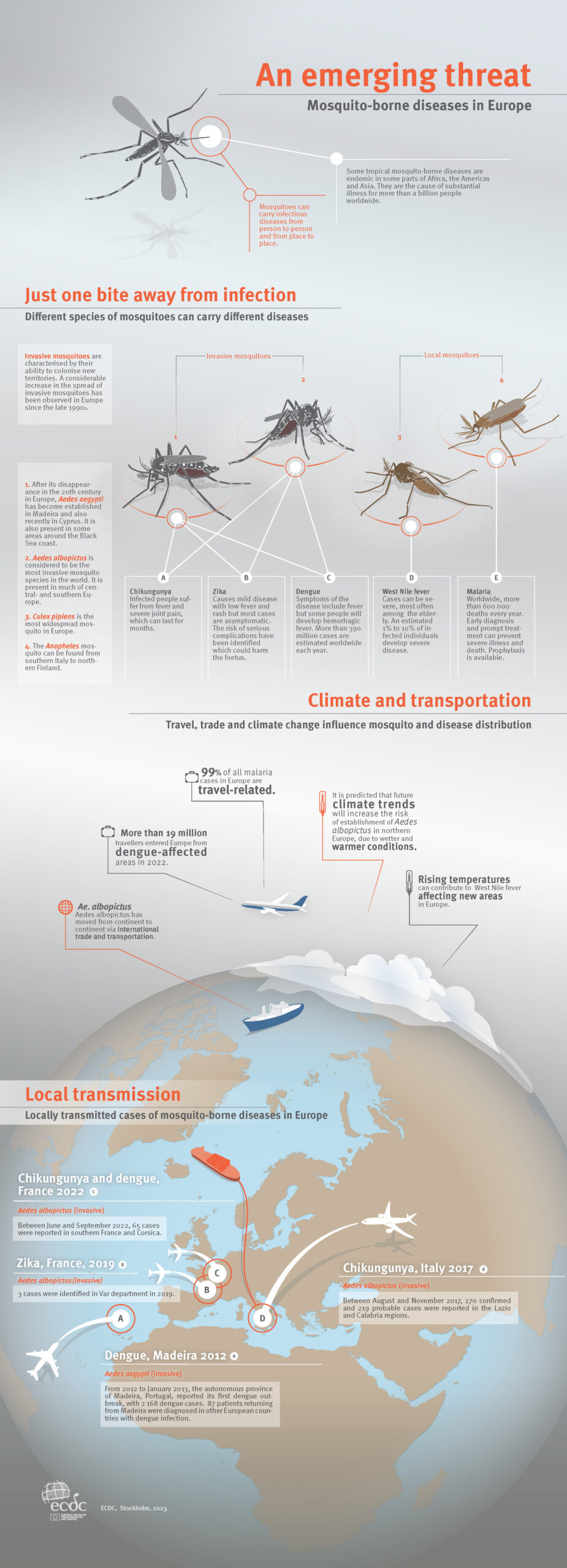

The tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), which can transmit the dengue and chikungunya viruses, is establishing itself further northwards and westwards in Europe, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

- Warmer climate, heat waves and floods making Europe increasingly hospitable to mosquitoes

- Higher risk of dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, zika and West Nile viruses

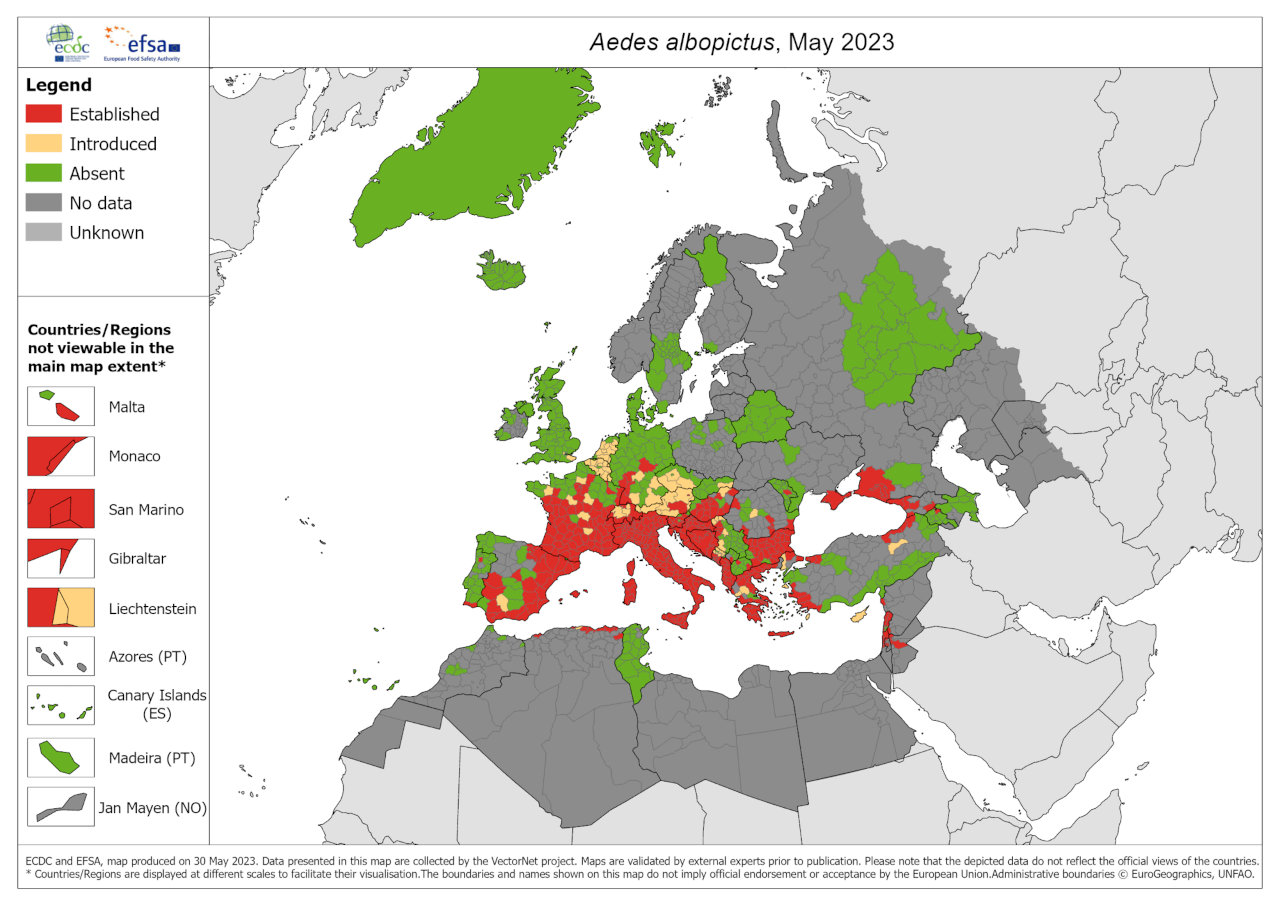

- 10 years ago, the tiger mosquito (Aedes Albopictus) was established in 8 European countries ‒ now it’s in 13

- In 2022, the ECDC recorded 1,133 cases of West Nile virus ‒ 92 people died.

- Last year, there were 71 cases of locally acquired dengue fever ‒ equivalent of the total number recorded from 2010 to 2021

Another mosquito species, Aedes aegypti, known to transmit dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, zika and West Nile viruses, has been established in Cyprus since 2022 and may continue to spread to other European countries, experts say.

Vaccines can protect against some, but not all mosquito-borne diseases. The first dengue vaccine became available in 2015, with a second one approved in 2022. A yellow fever travel vaccine is also available. Researchers are working on new vaccines against dengue fever, chikungunya virus, malaria and Japanese encephalitis ‒ all of which can be spread by mosquitoes.

Most cases of these diseases in Europe are recorded in people returning from regions of the world where the viruses are endemic. But that is slowly changing as mosquito populations grow in European countries. ‘Historically, these diseases were seen only as imported cases,’ said Andrea Ammon, ECDC Director. ‘Now we are seeing domestically-acquired cases.’

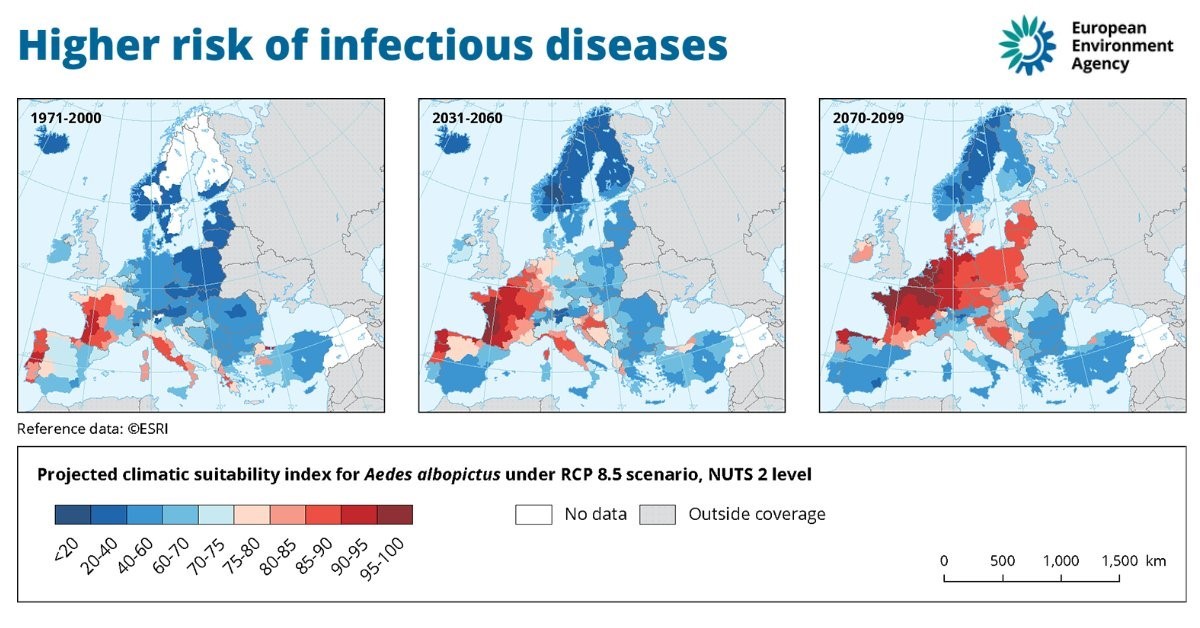

The ECDC, which has launched a report on mosquito-related illnesses, said Europe is experiencing a warming trend where heat waves and flooding are becoming more frequent and severe, and summers are getting longer and warmer. This creates more favourable conditions for invasive mosquito species, new data shows.

Ten years ago, in 2013, the Aedes albopictus mosquito was established in 8 EU/EEA countries, with 114 regions being affected. Now, in 2023, the mosquito is in 13 countries and 337 regions. This means that if someone returns to Europe from, for example, Asia, having been infected with a dengue virus, they could then be bitten by a local mosquito which may pass the virus to the next person it bites.

‘In recent years we have seen a geographical spread of invasive mosquito species to previously unaffected areas in the EU/EEA,’ said Dr Ammon. ‘If this continues, we can expect to see more cases and possibly deaths from diseases such as dengue, chikungunya and West Nile fever. Efforts need to focus on ways to control mosquito populations, enhancing surveillance and enforcing personal protective measures.’

Last year, the European Environment Agency published models forecasting a steep rise in mosquito populations throughout the 21st century. It shows that tiger mosquitoes could become established as far north as Ireland, Sweden and the Baltic states.

The number of people affected by mosquito-borne illnesses is already rising. In 2022, 1,133 human cases and 92 deaths from West Nile virus infection were reported in the EU/EEA. Of these, 1,112 were locally acquired in 11 countries, the highest number of cases since the peak epidemic year in 2018. Locally acquired cases were reported by Italy (723), Greece (286), Romania (47), Germany (16), Hungary (14), Croatia (8), Austria (6), France (6), Spain (4), Slovakia (1) and Bulgaria (1).

In 2022, 71 cases of locally acquired dengue were recorded in mainland EU/EEA, which is equivalent to the total number of cases reported between 2010 and 2021. Locally acquired dengue cases were reported by France (65 cases) and Spain (6 cases).

Read more: Will warmer climate mean more infectious diseases?

Celine Gossner, Principal Expert, Emerging- and Vector-Borne Diseases at the ECDC, told a press conference that the first detection of the tiger mosquito in Europe was in 1979. Experts are now seeing ‘continuous and rapid spread’ of the mosquito species. The more recent establishment of Aedes aegypti is of even greater concern as it has a ‘very high capacity to transmit viruses and it mainly bites humans’ (whereas some other mosquitoes bite a wide range of mammals).

Aedes aegypti’s presence in Cyprus has raised concerns that it may spread to Turkey and Greece. ‘We can expect more outbreaks of vector-borne disease, and for those outbreaks to be larger, particularly in light of climate change,’ Dr Gossner said.

Impact on health systems: blood shortages

There may be consequences for health systems that go beyond the need to manage cases in hospitals and in the community, she noted. As well as causing illness to individuals, dengue fever and West Nile Virus outbreaks also disrupt blood supplies in regions forced to pause blood donation during epidemics. As blood donors defer donations, there is a risk of shortages. Donated blood is used to treat people with anaemia, cancer and blood disorders, among others.

The ECDC said sustainable ways to control mosquito populations include eliminating standing water sources where mosquitoes breed, using eco-friendly larvicides, and promoting community awareness about mosquito control. Personal protective measures include the use of mosquito bed nets (preferably insecticide-treated nets) or sleeping or resting in screened or air-conditioned rooms, using window screens, wearing of clothes that cover most of the body, and the use of mosquito repellent.