As we age, our immune systems decline naturally. The process, known as ‘immunosenescence’, typically accelerates from the age of 50 onwards, making older people more susceptible to infectious diseases. It can even reduce their immune response to vaccines.

Experts in healthy ageing say this age-related decline is a threat to the effectiveness of vaccination programmes in Europe. And it may mean that vaccines for ‘older people’ should be given earlier than is currently the case. Most vaccination policies remain tied to chronological age rather than biological age, missing opportunities for prevention.

A new report published by the International Longevity Centre UK, says that with one in five Europeans now aged 65 or over, immune system ageing could be driving rates of hospitalisation.

‘As we age, our immune systems weaken, leaving us more vulnerable to diseases that vaccines could otherwise prevent,’ says David Sinclair, ILC-UK’s Chief Executive. ‘Yet our policies are still too often built around rigid age thresholds rather than the reality of how our bodies change over time.’

The report highlights how this mismatch between science and policy leaves millions of people vulnerable.

‘We need to invest in the science that helps us understand how our immune systems age, and in the preventative interventions that keep them strong,’ Sinclair says. ‘That means moving away from one-size-fits-all vaccination schedules, targeting protection where it’s needed most, and ensuring that older adults aren’t left behind.’

Staying healthy for longer

Vaccination rates among older people are below target in most European countries, although up-to-date data is not readily available. Across Europe, only 47% of people aged 65 and over received a flu vaccine in 2022 – leaving around 60 million older people unprotected. Pneumococcal vaccination rates are even lower, averaging just 24% in the ten countries with available data.

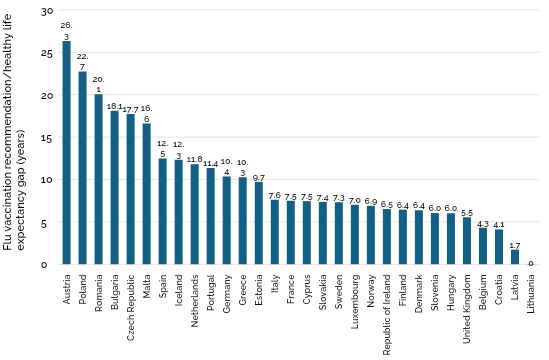

However, some countries have lowered their vaccination age recommendations in line with their average healthy life expectancy (HLE).

- In Bulgaria, flu vaccination is recommended for people aged 45 and over, while the HLE is 63.1 years. Bulgarians who are vaccinated against the flu at 45 can expect to live another 18.1 years in good health, which potentially allows for a better immune response.

- In contrast, Lithuania’s age-based recommendation is for flu vaccination to begin at aged 65 but has an average HLE of 65 meaning the average window of time living in good health ends at the point of vaccination.

- Average HLE in the UK is 70.5, yet the NHS recommends flu vaccination at 65, meaning there is a 5.5-year gap between the age at which someone becomes entitled to receive a free flu vaccination on the NHS and the age at which they can expect to live a “healthy” life.

Health inequalities compound the problem, says the ILC-UK. There is almost a decade (9.5 years) between the highest and lowest healthy life expectancy across Europe. Countries in Eastern Europe tend to have both lower healthy life expectancy and higher rates of long-term conditions. People in poorer regions face a double disadvantage – they are more likely to become ill earlier and less likely to access preventative care such as vaccination.

To close these gaps and help people stay healthy for longer, the report calls on national governments and EU institutions to act. Governments should:

- Lower the age for routine vaccination programmes such as flu to around 50, or in line with national healthy life expectancy, so people are vaccinated while their immune systems are still capable of a strong response

- Invest more in using and supporting the development of enhanced vaccines that deliver better health outcomes for older adults

- Increase the proportion of health budgets spent on immunisation and commit to spending at least 8% of healthcare budgets on prevention.

Finally, the report says the European Parliament should establish a new Sub-Committee on Healthy Ageing to lead a coordinated European approach.

‘Good health in later life isn’t just about living longer – it’s about living better,’ says Sinclair. ‘Keeping people healthy helps them to work, volunteer, care and contribute. Investing in prevention and tailored science isn’t a luxury – it’s essential if we want to unlock the economic and social benefits of longevity.’