In an ageing world, it’s never been more important for countries to invest in preventative health, not least because it means countries will be able to truly benefit from the ‘longevity dividend’. Yet despite repeated commitments by governments to invest in preventative health, action continues to lag.

This is where the Healthy Ageing and Prevention Index comes in.

The International Longevity Centre UK launched the Index in May 2023, alongside the 76th World Health Assembly. It is an online interactive tool that, for the first time, brings together health, wealth and societal metrics to compare how sustainable different countries are, both in terms of longer lives and the extent to which their governments are investing in efforts to prevent ill health and support healthy ageing.

Using pre-COVID baseline data from 2019, the Index ranks 121 countries against six indicators: life span, health span, work span, income, environmental performance, and happiness.

The data is pulled from various sources including the World Health Organisation, the International Labour Organisation, the World Bank, the Yale Environmental Performance Index and the United Nations.

The Index finds that:

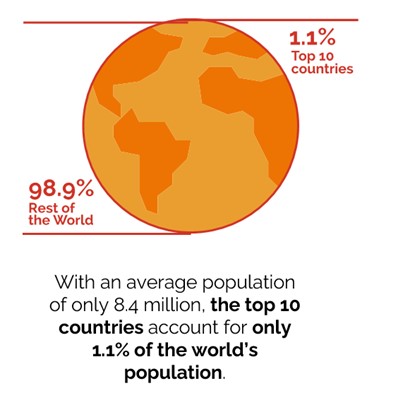

- The countries ranked in the Index’s top ten are Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Singapore, Australia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Denmark and Ireland.

- Of the top 20, only a third are non-European. These include Singapore (ranked 5th), Australia (ranked 6th), Canada and New Zealand (jointly ranked 13th), and Japan (ranked 17th).

ILC analysis also finds that there are significant health and wealth inequities between countries at the top and bottom of the Index.

Only the top 1% of the population is best adapted to longer, healthier lives:

And there are significant inequalities between the top and bottom of the Index across the metrics, including life span, health span, and work span:

The purpose of the Index is to hold governments to account on healthy ageing and their level of investment in prevention, as well as to identify areas for improvement and actions countries must take to improve their global ranking.

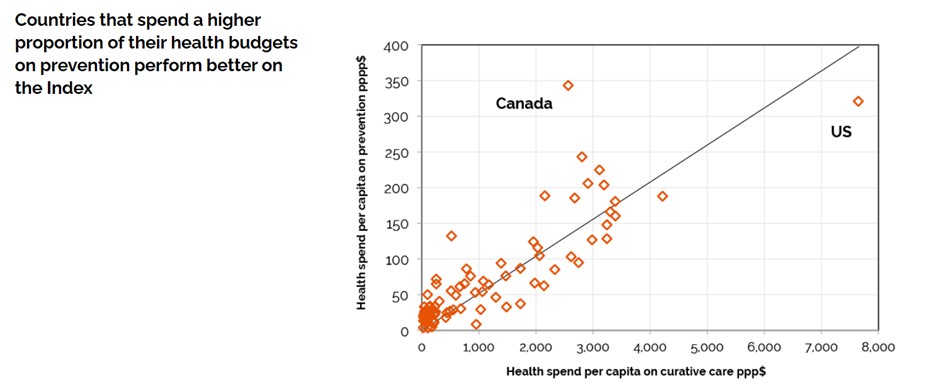

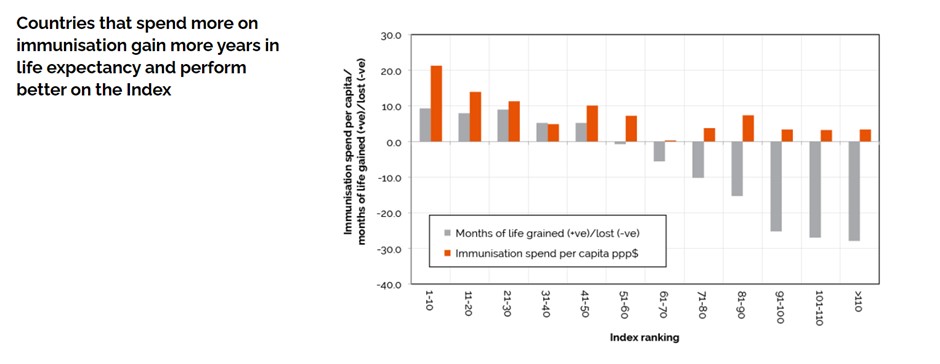

To achieve this, ILC-UK compares the Index with other factors (secondary metrics), such as immunisation spend and coverage. Our analysis finds that countries spending more on prevention, and specifically on immunisation, perform better than those who spend less.

Canada (ranked 11th) and the US (ranked 31st) are outliers, with Canada spending relatively more on preventative healthcare than curative healthcare, and the US spending a much larger proportion of their health budget on curative care than on prevention.

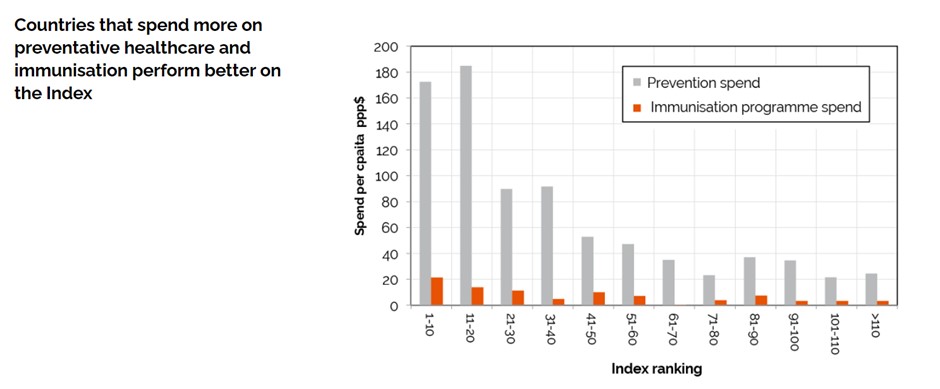

Higher ranked countries spend significantly more on prevention than lower ranked countries. While higher ranked countries still spend more on immunisation than lower ranked countries, comparatively, immunisation programmes make up a very small proportion of overall prevention spend. Considering that most immunisation programmes are targeted at children, adult immunisation likely constitutes a fraction of this already small amount.

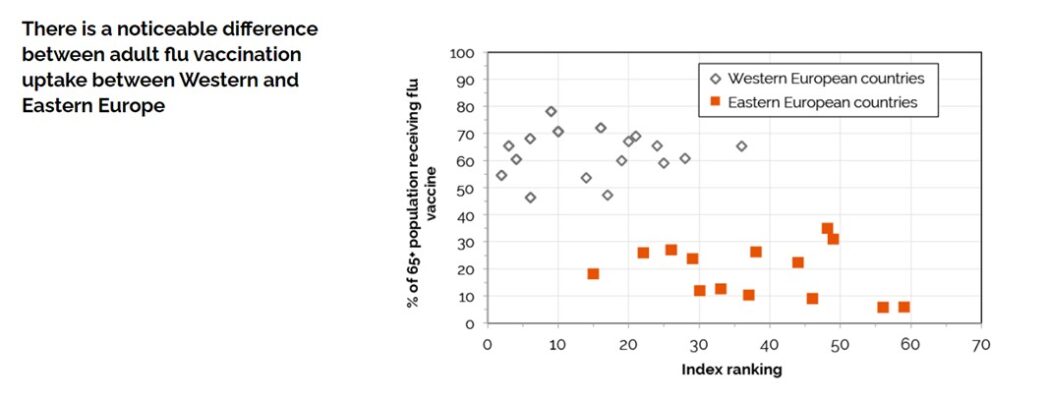

Countries in Central and Eastern Europe, including former East bloc countries, have considerably lower rates of flu vaccination than Western European countries and effectively form a distinct group. The top vaccinated country is Denmark (ranked 9th) with 75% and the bottom vaccinated country with only 5.8% is Bulgaria (ranked 56th).

The difference between life expectancy at birth compared with the first year or so of life is normally positive in a well performing health economy. But in less well performing countries, life expectancy at birth may be negative when compared with childhood life expectancy. For instance, you tend to see lower life expectancy at birth in countries with high infant mortality because high infant mortality rate has a negative effect on overall life expectancy.

Countries that spend more per capita on immunisation not only gain more years in life expectancy but also perform better on the Index. This suggests immunisation plays a critical role in improving life expectancy outcomes, leading to a higher Index ranking. In addition, this suggests that vaccination programmes may, in general, be underfunded in around half of all countries.

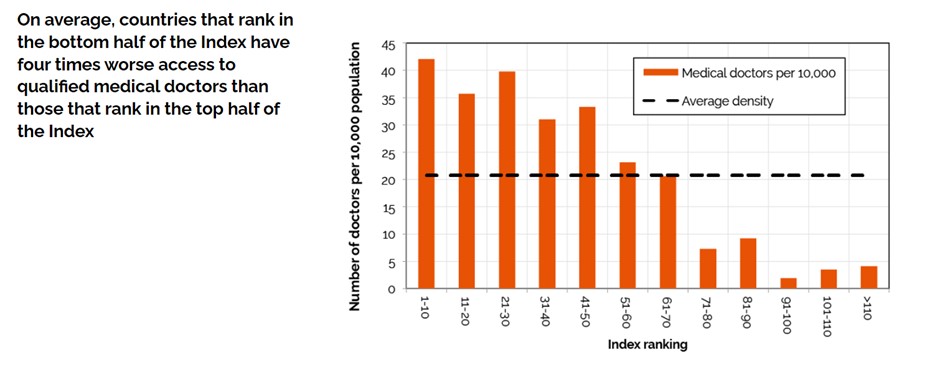

While there are many factors contributing to these differences, access to healthcare is a major barrier. We find that high ranked countries have the most medical doctors with over 40 per 10,000 population.

Countries ranked between 11-40 have around 35 per 10,000. However, those ranked 70 or worse fall to an average of only five per 10,000. According to the WHO and World Bank, at least half of the world’s population cannot obtain essential health services.

In addition to ranking countries, the Index ranks nine political and economic groups such as the EU, G7, G20 and OECD.

Alongside the Index, ILC has launched a Coalition that brings individuals and organisations together under a shared vision to hold governments to account on supporting healthy ageing by investing in preventative health. If you’d like to learn more about the Index, or join the Coalition, please check out the Healthy Ageing and Prevention Index.

Arunima Himawan is a Senior Health Research Lead at ILC-UK.