Warmer weather will give parts of Europe a ‘part-time tropical’ climate in the coming decades. This, in turn, will make large areas of the continent more suitable for mosquitoes, sparking outbreaks of dengue fever and chikungunya. The outbreaks will become larger and more frequent, impacting health systems and the tourism industry.

These are some of the stark findings of a paper published in Lancet Planetary Health, an academic journal, which looks at how climate trends in Europe will shape the rates of diseases spread by the Asian Tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus).

Professor Jan Semenza of Umeå University, Sweden, says a 1% increase in mean summer temperature is expected to lead to a 55% increase in the risk of outbreaks. (Scroll down to watch a full video interview with Prof Semenza.)

‘If we have a very moderate climate – with emissions control – the risk won’t go up dramatically,’ he says. ‘However, the track we’re on at the moment is an extreme emissions scenario. We see a five-fold increase in risk by 2060 with higher emissions and temperatures. So the situation will get much worse.’

Europe has already had cases of dengue fever, including a significant outbreak in Croatia in 2010. Last October, 213 cases were recorded in Italy in one of the largest epidemics in recent times.

The virus is widespread in tropical countries, including tourism hotspots in southeast Asia and Brazil. If an infected mosquito bites a European tourist in Thailand, the tourist may bring the disease home. In the absence of Tiger mosquitoes in Europe, the disease would not spread, but if the mosquito is present locally, it can bite the infected person and then spread it to others.

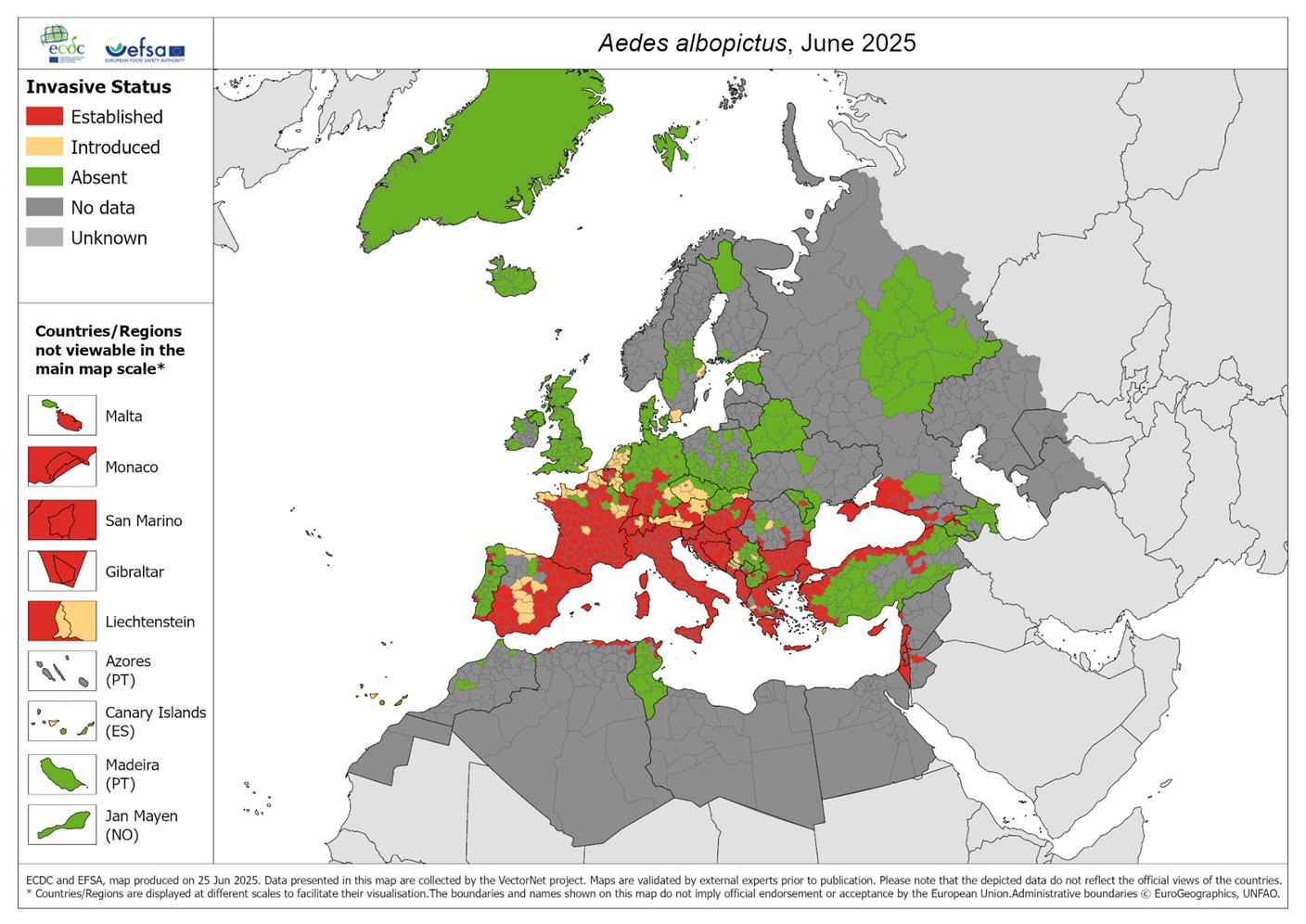

The Asian Tiger mosquito is an invasive species: they are not native to Europe but can establish themselves if the climate is hospitable. They were detected in Genoa in the 1990s and have spread throughout the Italian peninsula, before moving to France, Spain and Croatia. Mosquito populations currently die out each year when temperatures fall, but can be re-established.

‘The bad news is that it previously took twenty years between the arrival of the mosquito and an outbreak of disease, says Prof Semenza. ‘That timespan has collapsed down to five years today. The emergence of these infectious diseases has been accelerated by climate change.’

The time between outbreaks has also shrunk. In the past, it took 12 years from the first outbreak to the second outbreak. Now, the gap between outbreaks is one year. ‘And we’ve seen an exponential increase in the number of cases. The number of districts impacted is also increasing exponentially. This is a concern to all of us who work in public health.’

The potential health implications go beyond the direct impact on sick individuals and their need for medical care. For example, mosquito-borne diseases have the potential to affect blood supplies. ‘People donate blood, which is vital for clinical reasons. But if there’s a West Nile Virus outbreak, and someone who is asymptomatic donates blood, it could affect blood banks,’ Prof Semenza says. ‘If the virus is not picked up by screening, the blood distribution system could be affected, putting people at risk who are undergoing surgery.’

To curb outbreaks, find cases early

The most effective solution to all of these challenges would be to lower emissions and limit climate disruption. But health systems can still prepare for an adverse scenario in which temperatures rise and Tiger mosquitoes become common. Top of the ‘to do’ list: better surveillance.

‘The 2010 outbreak was not picked up in Croatia,’ Prof Semenza recalls. ‘A tourist went home to Germany with symptoms and was diagnosed there. The outbreak was then tracked back to Croatia but it had not been picked up locally.’

In all probability, the full number of cases was much higher than official figures indicate, and reporting of mosquito-borne diseases remains low across Europe. France and Italy have good surveillance, but others are less well prepared.

‘If you don’t know there’s an outbreak, you can’t contain it,’ he says. ‘We need to identify cases, make sure people get treated, and ensure that they don’t get exposed to mosquitoes because that drives the outbreaks.’

As the health and economic costs rise, policymakers should look at enhanced surveillance around airports, early warning systems for outbreaks, and discuss the options for using vaccines – either to contain outbreaks when they occur, or to protect populations should dengue or chikungunya become endemic in future.

Globally, vaccines that protect against dengue and chikungunya are already approved in some countries, with more currently being developed, but none are yet in widespread use, according to the WHO. Vaccination could, however, become part of a wider response in future.

Read more: Mosquitoes spread diseases to new regions of Europe

‘There are vaccines against dengue and chikungunya. Do we need to consider these in Europe? We’re not there yet. It’s something to think about if we are to meet the new normal when these diseases become endemic.’

Sound policies can make a difference. For example, Mexico and Texas have similar climates, but the incidence of dengue is much higher in Mexico. This may be because people on the US side of the border are more likely to use window screens, air-conditioning and mosquito repellant. Other protective measures include eliminating standing water in containers and tyres, which some mosquitoes use to breed. Europe may have lessons to learn from regions experienced in coping with these conditions.

What can Europe do?

Authorities are taking the problem seriously, even if the message has yet to strike a chord with the wider public. In July, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) launched a new series of weekly surveillance updates to help public health authorities monitor chikungunya, dengue, Zika, and West Nile viruses.

The ECDC says that last year, 2024, saw 304 cases of locally acquired dengue in Europe, an increasing trend compared with previous years (130 cases in 2023 and 71 cases in 2022). In the same year, 1,436 cases of West Nile virus infection were recorded, with infections spanning 212 regions in 19 countries. These figures underline the growing geographic spread and public health impact of mosquito-borne diseases in Europe

Other innovative approaches have also been tested. In Switzerland, for example, local authorities are releasing sterilised male mosquitoes in an attempt to crash the tiger mosquito population that might otherwise spread dengue and chikungunya. The so-called sterile insect technique (SIT) has been used since the 1950s to control fruit flies. Genetically-modified mosquitoes, and mosquitoes carrying bacteria that limit their breeding capacity, have also been bred for use in Brazil where dengue is endemic.

Cost of action vs cost of inaction

For the European tourist sector, outbreaks are a threat, as is the prospect of southern European destinations requiring travel vaccines in the decades to come. However, there is little appetite for public awareness campaigns or stronger public health responses, as these too may affect tourism.

The new paper shows where we’re headed and, say the authors, calls for a coherent policy response. ‘I wish we could have evidence-based policymaking, as opposed to policy-based evidence-making,’ Prof Semenza says. ‘The whole thing has been turned upside down. People are opposed to taking action, but we must make policy based on the facts.’