Scientists are working on vaccines that could help to solve one of the greatest public health challenges of our time: drug-resistant bacteria.

A dream has turned into a nightmare. Antibiotics, along with vaccines, were one of the greatest breakthroughs in medical history.

How can vaccines help?

Vaccines can help combat antimicrobial resistance in three ways:

- Immunisation can reduce the use of antibiotics in treating conditions such as pneumonia or pertussis. They therefore indirectly reduce the opportunities for resistant bacteria to develop. Vaccines against these conditions can also help to reduce hospitalisation.

- Immunisation reduces the misuse of antibiotics. Vaccine-preventable viral infections are sometimes mistakenly diagnosed as bacterial infections and treated with antibiotics. For example, antibiotics are sometimes prescribed for patients with flu or a heavy cold – even though they are ineffective against viruses.

- Immunisation may help prevent the development of resistant bacteria such as MRSA, C. difficile and others

But disease-causing bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics as quickly as new antibiotics are being developed. For some bacteria, only the strongest antibiotics are effective. For others, even the last line of defence has been breached: we are defenceless.

Bacteria naturally become resistant to antibiotics over time. However, overuse – and, in many cases, misuse – of antibiotics have given these so-called superbugs the opportunity to find ways to evade our best weapons.

So serious is the crisis that political leaders, such as the G7, recently called for greater action on AMR and the UK has offered a £10 million Longitude Prize for progress on this field.

The European Commission is currently working to update the 2011 EU Action Plan on AMR.

“Antimicrobial resistance is a crisis that must be managed with the utmost urgency,” says WHO Director-General Dr Margaret Chan.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron has described the problem in even more dramatic terms: “If we fail to act, we are looking at an almost unthinkable scenario where antibiotics no longer work and we are cast back into the dark ages of medicine.”

Science fights back

By making better use of the vaccines we have, we can reduce the risk of illness, hospitalisation and death. For example, too few Europeans are vaccinated against influenza and thousands of deaths from community-acquired pneumonia could be avoided every year through immunisation against influenza and pneumococcal infection– especially of older people.

In addition to the decline in pneumococcal diseases/pneumonia, fewer antibiotics are prescribed to children and we see less circulation of resistant pneumococcal bacteria in the environment.

Most European countries are not hitting their target of vaccinating 75% of at-risk groups against flu. And pneumococcal vaccination coverage for older people is lower in the EU than in the US. Around 60% of Americans have had the pneumococcal vaccine. In Europe, the figure is 10%.

Vaccines also have the potential to make an even more radical contribution to beating superbugs: researchers are working on new vaccines that would make us immune to superbug infection.

The search for a new tuberculosis vaccine has intensified as multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) continues to spread. There are around 500,000 new cases of MDR-TB every year. The disease requires a long and unpleasant course of treatment and can cause death.

The existing Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine was developed 95 years ago and is only partially effective. A new and more effective vaccine would be an enormous victory against MDR-TB. The WHO says 16 TB vaccine candidates are currently in clinical trials.

Another infectious bacterium in researchers’ sights is gonorrhoea. Gonorrhoea causes significant reproductive health issues around the world and also facilitates the spread of HIV. Gonorrhoea has become resistant to the treatments of last resort in 10 countries and may soon become untreatable. Progress on vaccine development has been slow but animal studies have shown promise for some candidate vaccines.

Safer hospitals

Perhaps the most urgent task of all is to find a way to prevent methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). This infection, mainly spread in hospitals and nursing homes, affects tens of thousands of Europeans every year. Patients are particularly vulnerable to MRSA infection during surgery.

In Europe alone, MRSA causes more than 5,000 deaths as well as clocking up an estimated €380 million per year in hospital costs, much of which arises from the 1 million extra days of hospitalisation it causes. The bug is simultaneously making our hospitals more crowded and less safe.

The need for a vaccine is clear although it has not been an easy puzzle to solve. At present, we are still several years away from an MRSA vaccine but there is reason for hope. At least one potential vaccine is advancing in clinical trials and others are in the early stages of development.

Another superbug spreading misery in our hospitals is C. difficile. This bacterium causes thousands of deaths every year but a number of potential new vaccines are in the works.

Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) causes the majority of urinary tract infections and is a leading cause of adult bacteremia and sepsis. Increasing multi-drug resistance among strains of ExPEC is a major obstacle to treatment, causing increasing numbers of hospitalisation and deaths. Development of a multivalent vaccine based on cutting-edge technology is in progress.

Keeping people out of hospital is a great way to reduce pressure on health services and reduce use of antibiotics. Future vaccines, along with existing vaccines against rotavirus, pneumococcal disease and flu, would significantly reduce hospitalisation rates.

Developing vaccines takes time but the clock is ticking.

Rise of the superbugs

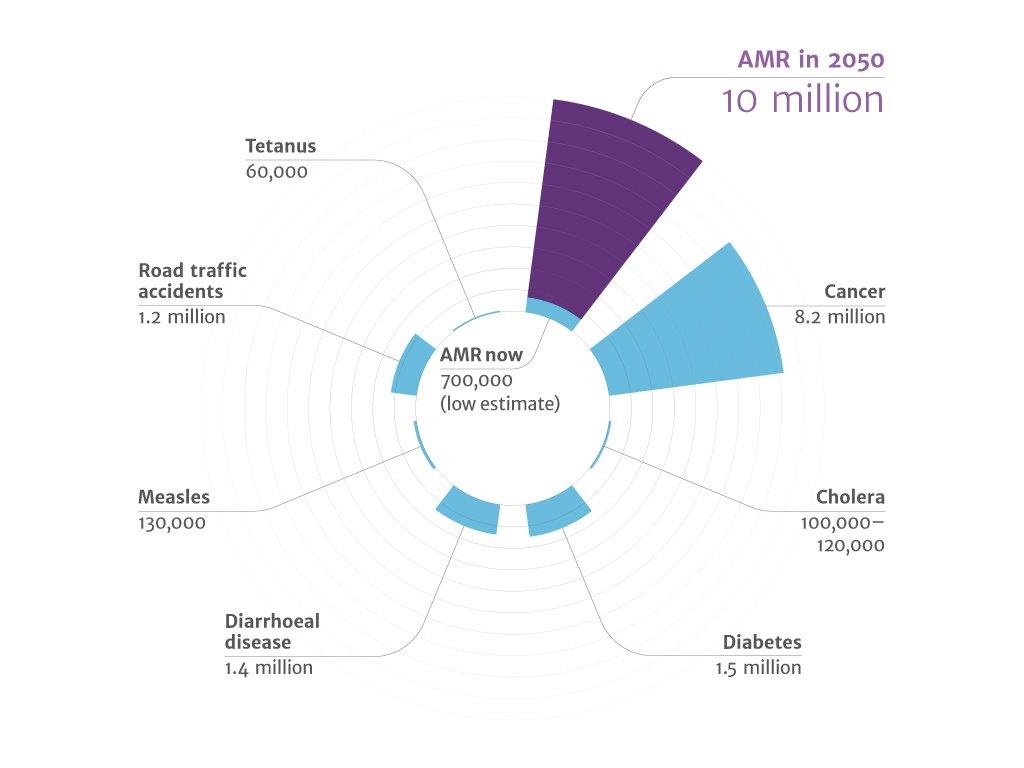

Antimicrobial resistance threatens to erode many of hard-won gains of medical science, according to the WHO.

Hospitals can be a breeding group for drug-resistant bacteria, making some patients sicker than when they were admitted.

“Antimicrobial resistance is compromising our ability to treat infectious diseases, as well undermining other advances in health and medicines,” the Organisation states.

The WHO Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance sets out five strategic objectives to tackling the crisis:

- Improving awareness and understanding of AMR

- Strengthening the knowledge and evidence base through surveillance and research

- Reducing the incidence of infection through effective sanitation, hygiene and infection prevention

- Optimising the use of antimicrobial medicines in human and animal health

- Developing the case for sustainable investment in new medicines, diagnostic tools, vaccines and other interventions.