On Sunday, 8 March 2020, Dr Oisin O’Connell was deeply worried. As a respiratory consultant at a large hospital, he watched with horror as Italian intensive care units (ICU) reached breaking point. O’Connell also has a doctorate in how the immune system responds to respiratory infections, so he was well placed to grasp what was coming down the tracks.

He had to do something. In his day job, O’Connell was frantically trying to prepare his hospital for a surge in demand and consuming every piece of evidence he could on how best to manage patients when the surge arrived. However, there was a sense that the public and politicians had yet to absorb the seriousness of the situation.

At that point, Ireland only had one community-acquired case of COVID-19. Schools, nightclubs and offices were open as usual, and the country was preparing for the annual St Patrick’s Day festival in mid-March. O’Connell recalls feeling a sense of urgency about connecting experts to one another, but also bringing evidence to policymakers and the public.

‘It was clear from conversations I was having with medical colleagues across the country that we needed a more nationwide platform for sharing key messages,’ he said.

So, he set up a WhatsApp group.

‘I knew hospital doctors and the heads of the medical and nursing organisations; I connected with GPs and pharmacists; I added any politicians I knew, including Simon Harris and Michael Martin,’ O’Connell explains. Harris was the Minister for Health at the time while Martin was the opposition leader and is now the Irish Prime Minister. Before long, Stephen Donnelly, who was then in opposition but is now the Health Minister was in. It was a well-connected group.

The Chief Medical Officer joined. Well-known scientists were added. Social scientists and historians of medicine were invited. Leading Irish and international experts based in the US, Italy, Chile, Australia and China provided vital data on how the disease spread and how it could be prevented. ‘Ireland is small,’ says O’Connell. ‘It’s possible to contact most of the key decision-makers in a crisis. Plus, our medical community is well connected globally as many of us spend time abroad early in our careers.’

Next came a number of prominent journalists and broadcast producers, using the group to find information on what was happening as well as interviewees for TV and radio shows.

‘I made the first 50 members administrators of the group so they could add anyone they felt was important ‒ after a week I no longer knew exactly who was in the group, except that we shared a common goal of responding to a crisis,’ O’Connell explains. ‘Any time a journalist reached out, we added them. Everything was considered open and public. We were pushing WhatsApp’s limit of 256 members for a single group, so I had to ask people to leave if we needed to add someone with particular expertise!’

It quickly became a key place to ask for help or offer advice. An open Google Drive was used to share data and papers, while an Irish doctor in China helped source COVID-19 testing kits and personal protective equipment (PPE) that his colleagues in Ireland were crying out for.

The sense of urgency that ran through the group fed into big decisions at political level. Four days after the group was established, Dr Leo Varadkar, then Prime Minister (now Deputy Prime Minister) interrupted a trip to Washington to announce the immediate closure of schools and a series of public health measures. The St Patrick’s Festival was cancelled, and the public began to feel the gravity of the crisis.

The government had thought to wait until the end of the week when Varadkar was due to return from the US, but instead the message that every day counts had been conveyed loud and clear. The WhatsApp group had, to some degree, added to the momentum behind the early announcement of dramatic control measures.

Building confidence at a time of uncertainty

Although few citizens were aware of the group, as the weeks wore on, it became a vital source of information for doctors and, via journalists, for the general public. ‘It was great to have members of the media in the group,’ O’Connell said. ‘From April to June 2020, if anyone expressed a strong opinion in the WhatsApp chat, they would be in three or four newspapers the next day or they’d be invited onto a morning radio show.’

One of the crucial successes of the group was its ability to connect the media with specific expertise. To meet the almost insatiable public demand for information on a subject of considerable uncertainty, a large number of expert voices was needed. However, it was crucial that these experts were offering a broadly consistent message: public spats between scientists on masks, social distancing and, eventually, vaccines, would have been deeply unsettling.

‘We all made sure our stories were straight, well-informed and time-sensitive when we went on the media and that helped contribute to public confidence in science and medicine,’ said Dr Ida Milne, a social historian who researches the history of infectious disease in the 19th and 20th century. ‘It also made the public less suspicious of vaccines when they became available.’

Milne’s expertise on pandemics of the past brought a unique perspective to the WhatsApp group. It also provided the public with some context for what was unfolding. This included the link between mass gatherings and mortality, which was evident from her own data on the 1918-1919 flu pandemic when end-of-war celebrations triggered a surge in cases and deaths.

In addition, the public was offered a more diverse roster of experts, beyond the daily interviews with the Minister for Health and Chief Medical Officer. In the week before social restrictions were introduced, Milne delivered a sobering but informative interview on a prime-time radio show as listeners were trying to make sense of what felt like an unprecedented situation ‒ but in fact, was old news to historians.

‘Ireland is small, and journalists are always looking for new perspectives when issues around vaccine safety arise,’ says Dr Anne Moore, a vaccine expert at University College Cork. ‘The WhatsApp group gave us a forum for discussion and a way to get other people’s perspectives when journalists had questions as the vaccine rollout began. We were always conscious that what we said in public could have consequences.’

Moore and Milne were also members of the ‘COVID Women’s Voices’ spin-off WhatsApp group which helped to air views and increase the impact of female expert voices on the airwaves. In addition, Moore joined a handful of vaccine experts that worked with the government’s Vaccine Taskforce, established in the winter of 2020. Chaired by Prof Brian MacCraith, a physicist and past President of Dublin City University, it played a vital role in rapidly drawing up a plan of action once vaccine deliveries were on the horizon.

‘Everything happened very quickly,’ recalls MacCraith. ‘We needed to bring together vaccine experts to share the science and build confidence before and during the rollout. We had to sit down with all the key decision makers to work out the logistics of delivering vaccines at unprecedented speed and scale. And, as there was no national immunisation information system, we urgently needed to develop one in real time.’

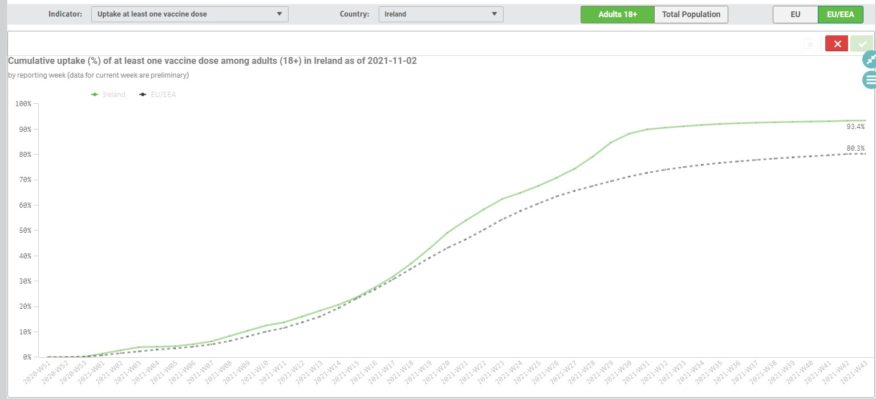

Today, more than 90% of people in Ireland aged 12 years or older are vaccinated and the country is now delivering third doses to vulnerable individuals, older adults and healthcare workers. Along the way, MacCraith’s taskforce helped to navigate multiple changes in the vaccine programme and the potential crises of confidence that struck every country with access to vaccines in 2020. Throughout, vaccine confidence held firm.

‘It became a national collective effort,’ he says. ‘People trusted the messages and the science. We tracked public sentiment on a weekly basis and ensured we got the right message to the right groups through the right channels.’ MacCraith says the authorities decided not to ‘take on the anti-vaxxers’. Instead, the focus was on providing high quality and consistent information in several languages via traditional and new media.

As decision-makers begin to look beyond the worst of the pandemic, MacCraith says the legacy of the work done a year ago will live on, particularly when it comes to the new IT system and general confidence in the vaccination system. ‘Trust in public institutions proved to be fundamental to the success of the programme,’ he says. ‘Beyond that, the key factors were collaboration, communication, confidence and convergence on a clear plan.’

In addition, public and private social networks of experts have been strengthened and could be reactivated should another public health crisis emerge. As well as being implicated in the spread of vaccine misinformation, it may be that social platforms can be harnessed for good. Perhaps, when the dust settles, they will even be viewed as a component of a resilient health system.

In the meantime, Ireland’s COVID Influencers WhatsApp group will be archived by the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland so that future generations can get a sense of how experts pulled together when faced with the public health challenge of their time.