The early signs were not good. France is a poster child for vaccine scepticism and surveys last year revealed a lack of enthusiasm for any COVID-19 vaccine.

In the 2016 Vaccine Confidence Index, France was the hesitancy hotspot. Just 41% of people agreed that vaccines are safe. A similar EU study in 2018 suggested some improvement but, as COVID-19 vaccines were rolled out, there was reason for pessimism in Paris.

There was no reason to hope that minds would change during a public health crisis. During the 2009/2010 H1N1 flu pandemic, vaccine uptake in France was abysmal. Even among GPs, flu vaccine uptake in 2010 was low. A study on attitudes to COVID-19 vaccines published in April 2021, predicted 29% refusal rates.

Real-world data

Of course, there has always been a gap between what people say in surveys and their real-world behaviour. Sometimes people say what they think the researcher wants to hear. On other occasions, they prefer to be contrarian before going with the flow when push comes to shove.

In 2016, when a majority of French people told the Vaccine Confidence Index that they did not view vaccines as being safe, vaccination rates were still close to 90% for many recommended vaccines. In the 2018 EU survey, less than 70% viewed vaccines as safe, but more than 85% said vaccines were important for children.

The findings offer more questions than answers. Were the surveys asking the wrong questions? Do a sizable number of French respondents think children should have an ‘unsafe’ medical intervention? Are people weighing up the risks and, accepting that nothing is perfect, following medical advice when invited for vaccination?

And what would happen when COVID-19 vaccines arrived in France?

Presidential intervention

At first, France more or less followed the EU averages, but there were worrying signs that some people were opting out; and concerns that younger people might not bother, thus prolonging the pandemic in France (while Denmark, Portugal, Ireland and Norway moved on).

These worries reached the highest echelons of power, prompting French President Emmanuel Macron to intervene. On 12 July 2021, he made a televised address to the nation, appealing to his compatriots to step forward for vaccination.

More than that, he introduced a series of concrete measures:

- Mandatory COVID-19 vaccinations for healthcare staff

- Vaccination campaigns for secondary school and university students

- The requirement to show a passe sanitaire (health pass) to enter public events

The passe sanitaire was seen as a game-changer. It required members of the public to be either fully vaccinated or to have passed a recent COVID-19 test. However, PCR tests for non-medical reasons (e.g. to facilitate travel or social activities) would no longer be free.

In August, the pass became a requirement to enter cafés, restaurants, shopping centres and for long-distance public transport.

The introduction of the pass sanitaire was greeted with protests in some quarters, adding further grievance to those already perturbed by requirements to wear masks or limit their social activity. France has enforced strict measures, including curfews, on several occasions during the pandemic.

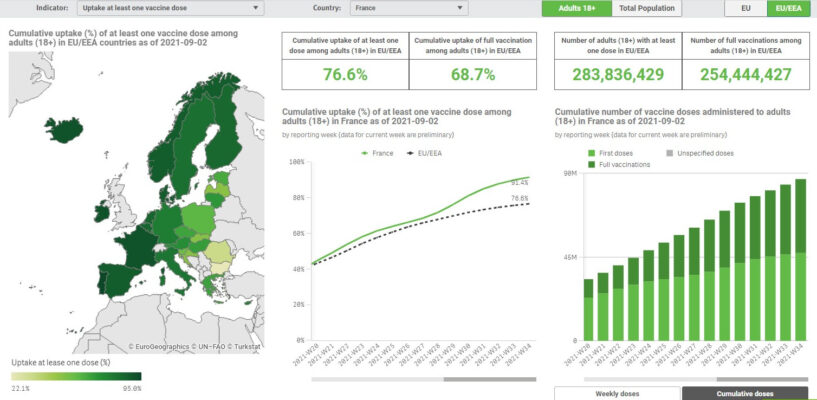

Despite some objections, the legislation supporting these measures was passed by the French parliament and widely enforced at the height of summer. As data from the ECDC Vaccine Tracker shows, France quickly began to diverge from the EU average. By the end of August, 91.4% of people in France had received their first dose compared to 76.6% in the EU.

Michaël Schwarzinger, a University of Bordeaux/Inserm researcher working on attitudes to vaccination, said the measure made all the difference. ‘COVID-19 vaccine uptake was much lower in France compared to other large European countries in early July,’ he said. ‘From 12 July, the President decided to enforce vaccination by introducing a compulsory passe sanitaire which effectively made vaccination a requirement for all social events. This led to a strong increase in demand.’

This was echoed by Dr Pierre Verger of the Observatoire Regionale de la Santé in southeastern France. ‘This [the health pass] gave a big boost to vaccination, even if there is a minority of the population that protests against it.

Dr Robin Ohannessian, a public health doctor and founder of TLM360, a telemedicine company, said there were mass protests against the pass but these were not necessarily anti-vaccine protests. ‘People want to go out, which can be facilitated by showing your pass,’ he said. ‘The easiest way to qualify for the pass is to have two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.’

For Prof Catherine Weil-Olivier, Honorary Professor of Paediatrics at Paris VII University, there were additional factors at play. Along with the health pass, positive data on vaccine safety and easy access to immunisation played a role. Furthermore, many people know someone who has been infected with COVID-19 and there is strong public awareness of the prevalence of the Delta variant.

‘Making an appointment at a vaccination centre was simple and convenient,’ she notes. ‘And whereas antigenic testing will soon require payment, vaccination is free of charge.’

France ❤ vaccines?

So, what does it all mean? Were French people not really particularly sceptical of vaccines? Were they just being obtuse when confronted with surveys on vaccine safety?

Or was the COVID-19 pandemic different because the threat was perceived as more immediate than the risk of flu, measles or HPV-related cancer?

In the end, perhaps France has not overcome its vaccine scepticism at all. It has simply revealed it to be a shallow sense of unease which was less entrenched than had been imagined.

Antipathy to immunisation is real but, apparently, it is of less value to people in France than the important business of socialising. ‘Santé!’