Scientists and video game developers have teamed up to create a variety of ways to communicate health information. The idea is simple: make it fun and people will be happy to play ‒ effortlessly learning key scientific concepts along the way.

Getting the balance right can be tricky. If so-called ‘serious games’ focus too heavily on education, they risk losing the entertaining elements that make great games so engaging. But if it’s all fun and no content, it does as much for health literacy as Super Mario Bros do for the public understanding of plumbing.

Collaborations between gaming experts, academics and health authorities have resulted in several promising approaches to using games to engage people in the challenging field of vaccine education.

The World Health Organization are among those testing how games can engage people in a place and format that they use regularly, rather than trying to attract the public to official websites. The aim, explains Andy Pattison, Team Lead, Digital Channels at the WHO, is to ‘get into people’s digital journeys’, bringing health content into games they already play or by collaborating with gaming companies to develop engaging games that build people’s knowledge and trust in vaccines.

‘The reason gaming is important to us is that it connects us with an audience we are trying to reach,’ says Pattison. ‘Traditionally, gaming has been particularly popular among young males playing games consoles, but there has been a surge in casual gaming on mobile phones among 25-35 women. This demographic has a strong role in making health decisions for themselves and loved ones.’

So, the big question: Do games work?

Researchers in Finland divided a group of students, with an average age of 15 years, into two groups. One group played the Antidote COVID-19 game (previously featured here and downloaded more than 50,000 times) while the other read similar information in a textbook.

‘Playing the game increased people’s interest in the topic more than reading the same content in a digital textbook,’ says Professor Kristian Kiili, Professor of game-based learning at Tampere University and lead author of the study. The gamers also reported higher levels of enjoyment and lower levels of boredom than those who learned solely through the written word.

The game-playing group reported higher ‘confusion’ but, explains Prof Kiili, this is common when playing complex games and can actually enhance learning by helping the player to focus attention on key information required to overcome challenges.

This suggests gaming can help to raise awareness and influence personal beliefs on health topics. ‘The findings demonstrate that health literacy games can be engaging and can increase adolescents’ interest in health topics ‒ such as vaccination ‒ more than text-based materials,’ Prof Kiili says. ‘Therefore, educators and health authorities should consider utilising games in health interventions and awareness campaigns, and in tackling misinformation. However, it is crucial that the games are well-designed and implemented.’

He said Antidote COVID-19 is a good example of a game in which the learning content and health information is ‘successfully integrated with appropriate game mechanics and elements’. In other words, health information is a natural part of the gameplay and not a detached thread that usually distracts the playing experience.

‘One important aspect of the game is that it allows players to experience the phenomena. For example, the players can experience how vaccines affect the human immune system and the coronavirus in the game, and how the behaviour of coronavirus differs from other viruses included in the game,’ he added.

The findings reflect earlier evidence collected by Psyon Games, the developers of Antidote, which show players will spend an average of 72 minutes engaged in the game. A previous version of Antidote was also used as part of a pilot HPV vaccine education initiative tested in a number of Finnish schools.

Immune Patrol: reaching 10-12 year olds

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe is working with academics and health authorities in several countries to pilot Immune Patrol ‒ a game designed to educate 10-12 year olds about infectious diseases, immunology and vaccines. The latest initiative was launched with the Armenian authorities, financed by the EU and Gavi, and supported by the University of Antwerp in Belgium and University of Aarhus in Denmark.

Immune Patrol is a ‘semi-digital learning game’ in which students work in groups in the classroom to figure out how to defend against infectious diseases. In addition to the online game, students can build a model of a cell, perform a drama about vaccinations, and use a virtual simulator to model the spread of disease.

A parent quoted by the WHO Europe says her daughter was excited to share what she had learned about diseases and vaccination. ‘She was especially impressed by the story of the smallpox vaccine, which was the first vaccine to be developed against a contagious disease,’ she said.

Psychologists at the Danish School of Education, Aarhus, are assessing the practical implications and learning outcomes of Immune Patrol in Ukraine, Denmark, the UK, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia and Moldova in a randomised controlled trial. The Copenhagen Game Lab, which helped to devise the game, says the initial results suggest that the gaming elements are more effective than traditional classroom teaching.

Classroom quizzes boost immunity

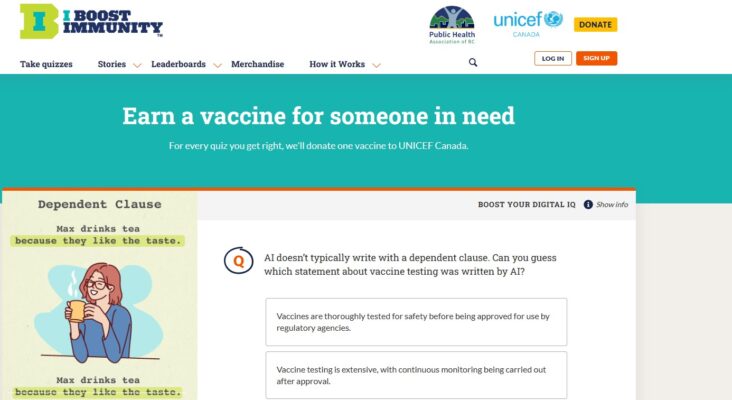

Finding innovative ways to bring vaccines to the classroom can support vaccine acceptance while bringing vaccines to those who need them. The Kids Boost Immunity (KBI) project, devised in British Columbia Public Health, combines education with altruism. Through lessons and quizzes school students learn about immunity, vaccines and critical thinking. When they score more than 80% on a quiz, a vaccine is donated to UNICEF Canada.

An independent evaluation of the initiative, published at the end of April 2023, looked at its impact to date. It shows that KBI has reached the classrooms of 4,745 teachers at 828 schools, plus a further 471 homeschool teachers. 98% of teachers said the quiz-based programme helped them to reach learning outcomes, with 95% agreeing that students had a positive response to learning about vaccines.

For students, the biggest appeal is earning vaccines for others. On that score, participants earned 317,000 vaccines. 73% of participating students said they are more knowledgeable about immunisation thanks to KBI.

The average participant takes 123 quiz questions, requiring significant commitment from students. Children are also using KBI at home, with 32% of time spent on the platform outside school hours.

A teacher quoted in the evaluation report says KBI continues to support ‘deep learning’ and classroom discussion, ensuring its impact goes beyond the initial rush of competing to answer questions and earn vaccines. ‘KBI challenges students,’ the teacher says. ‘These are not easy quizzes and topics; the students are forced to slow down, learn about a topic, and are incentivised to do so by knowing they are helping people around the work.’

Schools in Canada, the United States, Scotland and Ireland and elsewhere have registered for the platform, which builds on the I Boost Immunity (IBI) project through which more than 750,000 vaccines have been donated to UNICEF. IBI has been relaunched with a fresh focus on vaccine confidence, including new quiz questions on digital literacy and AI.

Evaluating impact

Children are not the only group to benefit from educational games. Research by Queen’s University Belfast shows that nursing students who played the Flu Bee game had a higher intention to get vaccinated. The study found that 84% of students that did not intend to get vaccinated before playing the game changed their minds after playing. This is one of several studies that has shown a positive impact of Flu Bee.

In addition to addressing understanding of immunology and perceptions of vaccines, games are being used to tackle misinformation. For example, Bad News ‘trains’ players to become purveyors of disinformation, helping them to recognise the tactics of those who deliberately spread falsehoods on social media. The game has been shown to confer ‘psychological resistance’ to online misinformation.

The Cranky Uncle game has been developed by scientists at University of Melbourne in Australia to teach critical thinking and build resilience against misinformation. It trains users to recognise and respond to science denial, highlighting the most common approaches of those who spread false information: Fake experts, Logical fallacies, Impossible expectations, Cherry picking, and Conspiracy theories (FLICC). The game has been adapted to address vaccine misinformation and, in partnership with UNICEF, the Sabin Vaccine Institute, and Irimi, is being used in East Africa, Pakistan and Ghana. (Vaccines Today will publish an article on this later in the year.)

Taken together, it is clear not only that there are several approaches to using gamification in vaccine communication and trust building, but that there is a growing trend to rigorously evaluate their impact. As this evidence builds, it has the potential to alter how public health authorities, schools and others engage with the public on vaccines and vaccination.