We’ve all read the headlines saying vaccination rates are too low. And, like many vaccine advocates, we’ve heard exasperated experts fret about disease outbreaks.

But if you take a step back – and a deep breath – the data show a strong trend towards rising vaccination rates. Yes, some of the graphs are a little bumpy but if you look at vaccine uptake on every continent in every decade, the picture is bright.

Take this beautifully simple animation from Our World In Data. It shows measles vaccine coverage for one-year-old children since 1980.

In developing countries, access to vaccines (and data keeping) has improved dramatically, thanks to initiatives such as the WHO/UNICEF’s Expanded Immunization Program and the work of GAVI and other non-governmental organisations.

The situation is also good in developing countries. Play the animation while looking only at Europe and watch the phenomenal progress that has been made. Yes, there is still work to do – measles has yet to be eliminated in Europe – but there is reason for optimism.

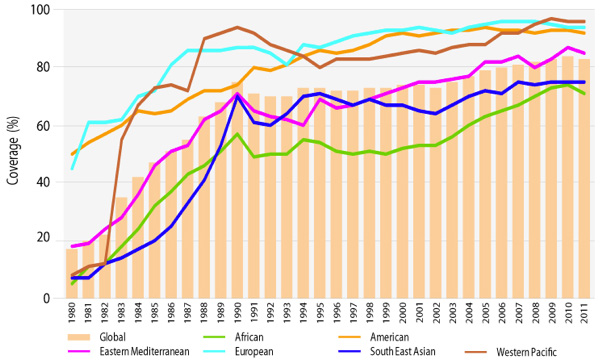

This graph of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccination rates should be equally inspiring.

After a surge in the 1980s, the global trend flattened out in the 1990s before lifting a little in the past decade when Africa caught up with south-east Asia. There is still room for improvement but the tools and the knowhow are there to make it happen.

Vaccines work

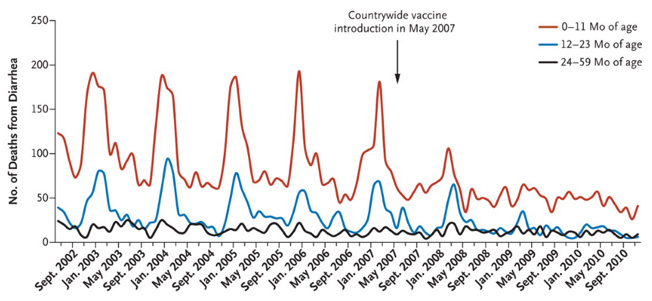

Crucially, the increase in vaccination rates leads to a decline in sickness and death. When Mexico introduced the rotatvirus vaccine, childhood deaths (for kids under five years) from diarrhoea fell by 56% over the course of three years.

Of course, the worried headlines and the concern we all feel when there’s a measles outbreak in Germany or a fatal case of diphtheria in Belgium are entirely justifiable. One death from pertussis is one too many.

These infectious diseases have a nasty habit of coming back when immunisation rates fall.

Indeed, these stories are heart-breaking and sometimes just infuriating.

The reasons for our impatience are straightforward. It is hard to believe that even a small number of people would opt out of something that is freely available and recommended by experts (and by their own doctor).

And, because the choice not to vaccinate can affect others, we have a direct interest in vaccination rates in our communities.

(To understand why we need all healthy people to be vaccinated, watch this animation on ‘herd immunity’).

Europe really, really, should be measles-free by now. Cuba is measles-free. Colombia is measles-free. How can Italy or France keep falling short?

As long as there are enough opt-outs or pockets of the population where vaccination rates are low, viruses like measles will continue to spread – perhaps even to people too young or too sick to be vaccinated.

So we will continue to push for optimal uptake of the vaccines recommended by health authorities and scientific societies. But we mustn’t forget the great strides that have been made.

Past successes are at the heart of our current frustration. They should be taken as a source of inspiration.

Play your part: check your vaccine schedule here or ask your doctor if you are up to date

Read: Vaccines accelerate fall in childhood deaths

Blog: Nobody should die from measles

More: Our World in Data – Vaccination

Gaylene

September 13th, 2016

Another graphic illustration is seen in graveyards. Before vaccines were commonly available, many children died. Parents feared outbreaks of diseases we can now prevent and embraced vaccines wholeheartedly. I am so grateful that my children were vaccinated.

Gary Finnegan

February 6th, 2017

Well put Gaylene. I’m also very glad to have mine protected.