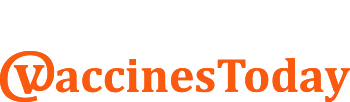

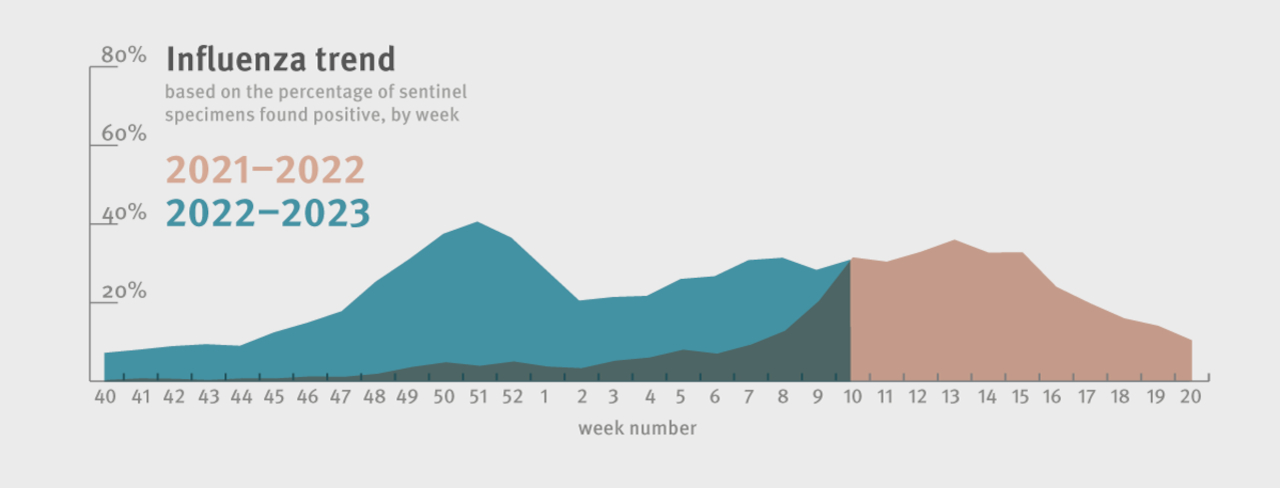

The annual flu season often arrives in winter and rises to a peak, before declining until the following winter. Last year, it came late. This year, it was early.

However, while the 2022/2023 flu wave appeared to have hit its peak around Christmas time, that was not the end of the story. The number of flu cases plateaued in late January before ticking upwards again.

It appears this flu season in Europe will have twin peaks. That’s not unheard of, but it’s worth noting that last year’s Australian flu season came early but had one big peak. Europe often looks to the southern hemisphere for clues as to how influenza epidemics might play out.

The question is: what is driving the recent increase in cases across Europe?

Data from the ECDC suggest the second wave is largely due to increased circulation of type B influenza virus. Overall, influenza A(H3N2) viruses have dominated the season, but there has been a late surge in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza type B viruses.

Let’s back up a little to look at the names of flu viruses. The H and N parts of the virus are commonly used to name influenza A viruses. The H in the names of these viruses stands for Haemagglutinin, a protein found on the outside of flu viruses that attaches it to the cells in our body. The N in the name of flu viruses means Neuraminidase, a family of enzymes. Both (particularly Haemagglutinin) are targets for flu vaccines.

Once attached, the virus can open the door to the cell, take over its internal machinery, and turn it into a virus factory. Your cells begin to produce lots of copies of the virus which spread through your body.

When cells copy viruses’ genes, they sometimes make mistakes. Errors in the H and N proteins are common and give rise to new viruses. In fact, when an animal or person is infected with more than one virus at once, they can produce a new virus that combines parts of both.

‘Because of this high error rate, we see constant change in viruses which necessitates frequent updates to the vaccine,’ Dr David Wentworth, Chief of virology surveillance at the Influenza Division of the US CDC told a WHO webinar earlier this month. ‘Some of these changes are a disadvantage to the virus; other times it benefits the virus in evading the host.’

The A viruses commonly found around the world include A/H3N2 which caused the 1968 flu pandemic, and A/H1N1pdm09 which caused the 2009/2010 pandemic. The influenza B viruses follow a different naming system. The most common B viruses are B/Victoria and B/Yamagata. However, detection of these B viruses has been much lower in recent years. Some were even beginning to wonder if they might be on the verge of extinction. But their contribution to the European double-barrelled flu season suggests rumours of their death may have been exaggerated.

New flu viruses are a pandemic risk

The tendency for flu viruses to change pose a risk of pandemics. Flu viruses that can infect birds (notably A(H5)) are a particular concern. These animal viruses usually do not infect humans. In most cases where an avian virus infects a human, there is no further human-to-human transmission.

This was the case in the recent avian flu cluster in Cambodia, for example, in which an 11-year-old girl died.

‘The majority of zoonotic infections from animal to human are self-limiting, with just one or two cases. Those viruses don’t take off,’ says Dr Richard Webby, Director, WHO Collaborating Centre for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds. ‘But when they do, we have a pandemic.’

He said the overall threat from zoonotic influenza is ‘not subsiding’ and scientists must stay on top of which viruses are circulating and be prepared to develop vaccines if required.

Dr Sylvie Briand, Director of Epidemic & Pandemic Prevention and Preparedness at WHO, said the most likely origin of the next pandemic is a virus that jumps from animals to humans.

‘In the event that it’s an avian flu virus, we need to be ready to protect people around the world through vaccination,’ she said. ‘The goal is not only about protecting against seasonal influenza, but anticipating potential new pandemic flu viruses to make the world a safer place.’