Given the severity of the current crisis, taking countless lives and sending our socioeconomic systems to the brink of collapse, it seems unimaginable that anyone would reject a Coronavirus vaccine. Yet, over the last two decades, vaccine hesitancy has risen so substantially that the WHO now considers it a major threat to global health.

Because some communities are refusing vaccines, old enemies once thought conquered are returning. Last year, for instance, the US saw its highest number of measles cases since 1992, nearly costing the nation its elimination status.

Reasons for vaccine hesitancy vary, but most stem from a case of cultural amnesia. Vaccines work because they shield our bodies from disease. But in doing so, they also shield our minds. Most of us have never experienced anything close to the fear and uncertainty created by COVID-19. But similar crises have occurred throughout history.

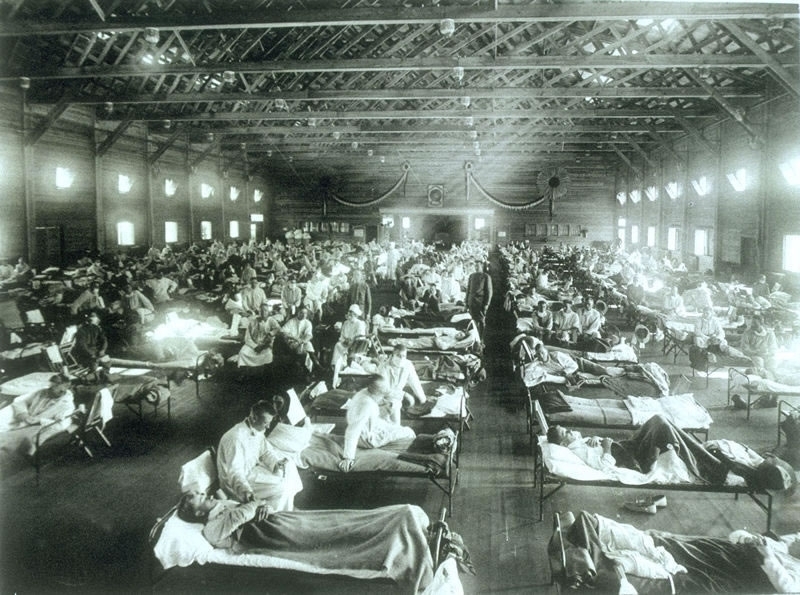

In 1918, an influenza pandemic erupted across the globe, killing 50 million people in its wake and hospitalizing countless more. Polio terrorized the US for most of the first half of the 20th century, striking abruptly and paralyzing generations of children. Smallpox, a deadly and disfiguring disease dating back to the 3rd century BCE, was finally eradicated in 1980 through vaccination.

Vaccines largely erased fear of these diseases from our collective consciousness; along with it, our sense of appreciation. Now, however, that fear has been rekindled. We have once again been forced to grapple with our own human frailty in the face of a viral pandemic for which science does not yet have a solution.

But out of this uncertainty, we have united in a manner that holds future promise. Even in cultures that pride themselves on individualism, it is inspiring to see so many readily make sacrifices to protect what we hold dearest: each other.

If a COVID-19 vaccine is developed, it is easy to envision our collective spirit translating into a renewed immunization movement— driven not by government coercion, but rather by voluntary action predicated on a revived understanding of the threat these diseases pose—both to ourselves and to humanity.

Hopefully, vaccination will be viewed for what it is; an act of civil service taken to protect not only one’s self but also those most vulnerable within our communities, including those who serve on the frontlines. Poorly accepted vaccines such as influenza—a disease responsible for >60,000 deaths in the US last season—might be viewed as the only sensible choice in a new era of social responsibility.

Nevertheless, if we do enter a renewed age of vaccine appreciation, how long will it last? As years pass, will we inevitably fall into the same pattern of apathy until the next pandemic strikes? History tends to repeat itself and there are no easy fixes. Our best hope, as always, is education. After this crisis ends (and it will), we must commit ourselves to reminding new generations how a small viral genome overcame centuries of scientific progress and nearly toppled the world as we know it.

The scientific basis for vaccination’s success is the concept of immune memory. Vaccines train our immune systems to fight infections before they invade. For some vaccines, the memory of how to fight lasts a lifetime. For others, it fades, requiring periodic boosts.

After COVID-19, will our memory of this pandemic sustain our sense of obligation towards one another, unite us in a shared fight against infectious disease, and encourage a lasting commitment to vaccination? Will our memory fade or will it last forever? For humanity’s sake, I hope it is the latter.

Alex Hartlage, PhD, an MD candidate at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, wrote this piece on behalf of Vaccine Ambassadors. This article is cross-posted from Global Health Now