Localization of global initiatives, such as efforts to build confidence in vaccines and the systems and people that deliver them, is still top of mind for many international governmental and non-governmental organisations.

Engaging communities and building their trust is a critical step towards building vaccine acceptance and driving demand for preventive immunisation services. Vaccination-related misinformation and disinformation erode public trust, negatively influencing vaccination decision-making and subsequent behaviour. Novel and contextualised behaviour-change interventions including those addressing rumours and misinformation are required to tackle this challenge.

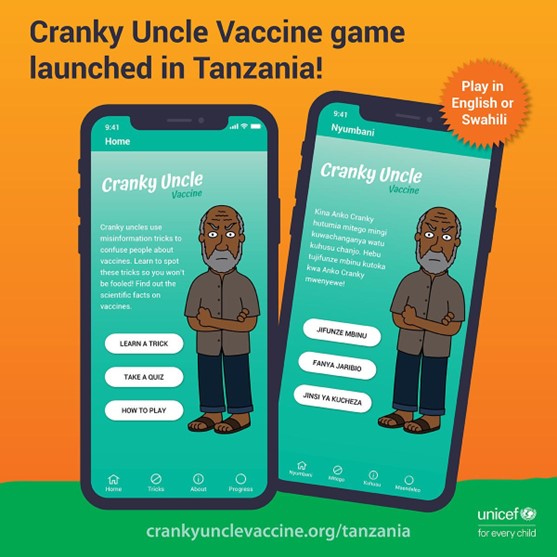

We saw this play out in the adaptation of the recently released game “Cranky Uncle Vaccine,” which offers both an engaging online and offline tool to combat vaccine misinformation, fostering resilience. We used a highly collaborative process in adapting the game for local relevance, which showcases the effectiveness of intersectoral partnerships in co-designing locally deployed solutions.

Originally created by global misinformation expert and University of Melbourne Senior Research Fellow Dr John Cook, “Cranky Uncle” uses cartoons, humour and critical thinking to expose the misleading techniques of science denial and to build public resilience against false narratives or arguments. Initially developed to counter climate change scepticism in high- and middle-income countries, “Cranky Uncle” uses “inoculation theory” which suggests that sustained exposure to a weakened form of misinformation can lead to a lower chance of being misled.

The concept of a vaccine version of the game was conceived early in the pandemic by Dr Angus Thomson, Principal and Senior Social Scientist at Irimi, a behavioural science firm, together with Cook while they were developing global guidance for UNICEF and country partners on misinformation management. Sabin Vaccine Institute joined the collaboration with additional seed funding and assisted with tailoring the game to local contexts, evaluating the game’s ability to improve users’ ability to distinguish between facts and fallacies and gauge their intention to vaccinate.

Sabin’s Vaccine Acceptance & Demand team then engaged with social and behaviour research grant partners in Kenya and Uganda and UNICEF Rwanda to develop a tailored version of the game. In-country co-design workshops were conducted with local partners in each country with potential target audiences – youth, parents and child caregivers, and health workers.

What became immediately obvious through discussion with participants was that if we had not centred community involvement in our process, we would have ended up with an entirely different product. And, that product would have likely been less effective in engaging the target populations.

Advice from community members would prove critical: They cautioned that specific character gestures or colours signalled specific political affiliations, which would be better avoided. They also requested more information about vaccination – in the form of a “protagonist” to counter our “Cranky Uncle’s tricks” and shared which type of health worker would be most trusted to deliver vaccination facts in the game e.g., doctor, nurse, community health worker, etc. We recognised quickly that people wanted to see themselves in the game.

The feedback from local participants also made it clear that we needed to simplify the script and use more colloquialized phrases or words for concepts to be better understood. For example, “if you eat goat, you will grow a beard” replaced “if you eat fish, you will grow gills”.

The real-time community vetting of the game ultimately yielded a more representative product. The end goal was to demonstrate a positive shift in vaccine attitudes and intent to vaccinate. In settings where the game has been piloted nationally, desired results such as changes in vaccine attitudes and discernment between vaccination facts and fallacies are being seen.

A similar process of co-designing with communities was used in adaptations for Tanzania, Ghana, and is now underway in Pakistan. We are developing a partner “playbook” to provide guidance for further local adaptation and adoption of this intervention in other regions and countries.

We found that guiding collaboration from partners in education, technology, design, and the public works well to combat misinformation and create a useful tool. Co-designing solutions and facilitating community participation is time-intensive but creates a relevant and community-responsive intervention that can be scaled with local buy-in.