The historic task of developing and producing billions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines has tested science to the limit. From the beginning, there were a series of barriers to successfully delivering vaccines against a disease that was unknown to most until 2020.

Now that several vaccines have navigated the path from development to regulatory approval, attention has turned to manufacturing. The goal is simple: make more vaccines, and make them quickly. Of course, the reality is far more complicated.

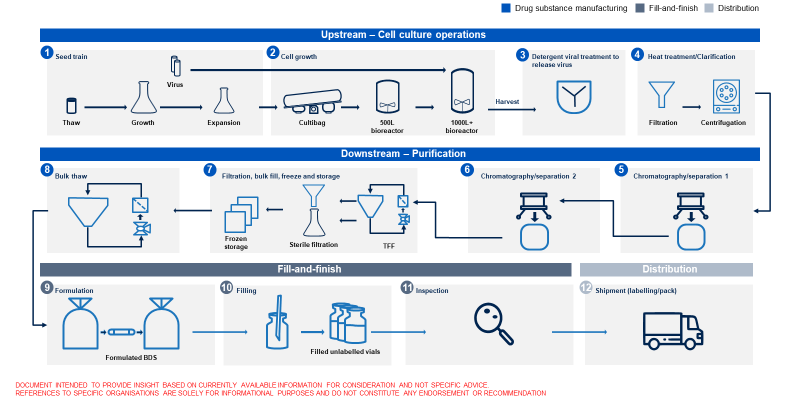

There are several key steps in making vaccines:

- Manufacturing the active ingredient (e.g. the coronavirus spike protein or the genetic code for the spike protein)

- Manufacturing of excipients (e.g. preservatives and stabilisers)

- Formulation (combining the products mentioned above)

- Filling and packaging (large batches are packaged)

- Release (batches are approved for release)

- Fill & finish (vaccines are put into vials, labelled and packaged for distribution

Along the way, dozens of quality control tests are performed. As some steps in the process involve biological products, there is a degree of unpredictability in the early stages of establishing a new manufacturing facility.

It is essential that the product is sterile and kept at the required temperature during manufacturing and transport. Scientists fine-tune the process to ensure they get the maximum yield, while maintaining quality and safety.

All of this takes time. Under normal circumstances, manufacturing plants spend years developing and perfecting production. With the world waiting for COVID-19 vaccines, time is in short supply. Once vaccines were approved, demand was high and immediate.

The optimisation process that scientists usually work through before a product is launched is happening now. This goes some way to explaining the uncertainty seen in producing millions of doses in early 2021, and why production has been increasing steadily as plants gain experience making the new vaccines.

Again, quality and safety remain paramount, but efficiency is a work in progress. It normally takes between 90 and 120 days to make a batch of COVID-19 vaccine, although this may fall over time. For example, the time taken to produce mRNA vaccines could be reduced from 110 to 60 days.

Limiting factors

Figuring out how to make vaccines more efficiently will significantly improve the prospects of delivering the billions of doses needed to meet demand in 2021. However, there are other factors that can slow progress.

For example, all the raw materials needed to make vaccines, from chemical ingredients and specialist machiners to filters and glassware, are in short supply. COVID-19 vaccines will use around 15% of the world’s supply of glass vials this year.

Manufacturing of lipids – tiny droplets of fats used to package mRNA in some vaccines – is expanding globally. But, if any ingredient or material is missing, production stalls until every item in the recipe is available.

The number of vaccine factories has increased steadily since the pandemic struck, but building specialist production lines (which have to be quality approved by regulators) is also time consuming.

Partnership is a fast-emerging solution: pharmaceutical companies that have not developed COVID-19 vaccines are teaming up with vaccine makers to expand global production capacity.

Final step

Development and production are, of course, not the end. Vaccines must be transported and stored at low temperatures. Countries receiving vaccines need to decide who will receive the first doses and who will administer them.

Many countries have turned large buildings into mass vaccination centres, with some using networks of doctors and pharmacists to deliver vaccines. As supplies grow, training health professionals to administer vaccines is essential.

And then, finally, it is important to think about the other end of the needle. Much of the conversation about ‘demand’ for vaccines has referred to demand from governments and health systems. But the key will be sustaining demand among the public.

To date, early concerns that significant numbers of people would opt out when offered a vaccine have not yet translated into widespread refusal. Despite surveys last year suggesting this would be a major problem, uptake has been good. As Dr Julie Leask, an expert on vaccine uptake behaviour has remarked, confidence tends to increase in countries once vaccine programmes get under way.

However, people who are high priority for the vaccine may have stronger motivation than some younger, lower risk individuals. Maintaining high levels of trust in vaccination is essential.

Manufacturers have safely produced and delivered hundreds of millions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines. This should contribute to public confidence in the months ahead.

If all goes well with the production of existing vaccines and of those in the final stage of development, an estimated 14 billion doses could be produced by the end of 2021. This would be three times the previous annual vaccine output.

With 40% of manufacturing capacity located in Europe, the availability of vaccines should grow steadily as production ramps up. All adults in Europe should be offered a vaccine by the end of the summer, while donations to the COVAX facility are expected to increase significantly later this year.

Whether plants will need to adapt to making vaccines against new variants remains to be seen. If so, the experience gained in scaling up COVID-19 vaccine production will pay off in the months ahead as any changes would be relatively minor.

The pandemic has significantly advanced capacity and knowledge of making billions of vaccines in record time, helping to prepare for future outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens that might arise.